Limited levels of accountability and duplication of activities by water actors led to suboptimal results in the Albert Water Management Zone for years. This trend has now been broken as government bodies, NGOs, CSOs, communities and private sector players have started working together and increased their efforts to jointly monitor water management interventions.

The Albert Water Management Zone (AWMZ) covers approximately 56,600km2 – 1.4 times the size of the Netherlands – and stretches across 42 districts of Uganda. With its size, including four main water basins and a significant number of river catchments, proper coordination within the AWMZ is of great importance. Lydia Biira, WASH officer of IRC Uganda, however shares that stakeholders rarely worked together: “Initially, NGOs, CSOs, [and the] private sector, would work on their own. They would work in silos, they would never have a forum where they would meet, nor safeguard collaborative efforts together.”

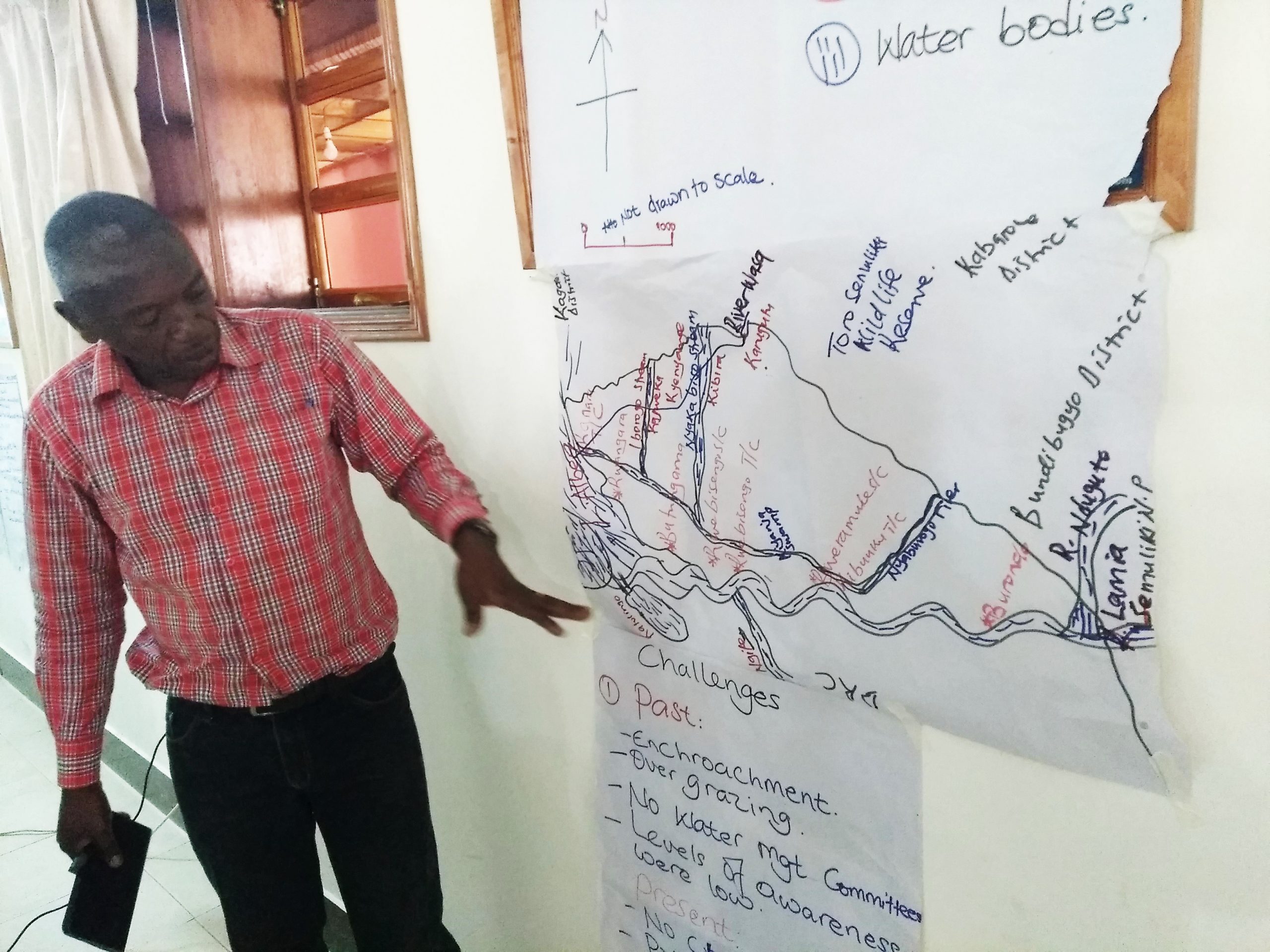

Therefore, coordination and collaboration in the AWMZ have been key points for the Watershed Empowering Citizens programme in Uganda. The programme brought water actors together, improved the capacities of Catchment Management Committee (CMC) and supported the development of Catchment Management Plans. Richard Rwabuhinga, District Chairperson for Kabarole and head of the Mpanga CMC, explains the value of the programme: “District committees are not well funded, but Watershed supported us by bringing actors [of the Mpanga catchment] together, ensured the coordination between the actors and supported us with the development and implementation of the Catchment Management Plan.” The team leader of the AWMZ, Brian Guma concurs with Rwabuhinga: “We came to realize that we are serving the same people and we have transitioned to catchment-based water resource management whereby we involve all the stakeholders in managing the water resources.” The coordination is now assured as the AMWZ will continue to chair the Catchment Management Committee.

For the Watershed programme partners, increased coordination and collaboration took time and patience. Lydia Biira from Watershed partner IRC underlines that advocating for integrated water resource management requires a different approach from both government and civil society: “Some of our advocacy work may sometimes look like it is attacking duty bearers, so we have to make sure we package our message very well.” She continues: “Most NGOs work in their own space, but now we had a space whereby we openly discussed workplans and aligned activities within the Catchment Management Plan. We couldn’t do that without emphasis on coordination.” An infamous story that reminds of the past times is the loss of a District bulldozer as a CSO tried to dredge a river without consulting the Catchment Management Committee and local authorities. The machine was never exhumed and remains a silent witness of the previous lack of coordination between actors in the AWMZ.

The stakeholders have however left these kinds of practices behind. Richard Rwabuhinga explains how collaborative actions now positively affect communities in the area: “We have worked together to confront the problem of riverbank management. For example, upstream [river Mpanga] we have been promoting good soil conservation practices and people who have been involved in stone quarrying are now in productive agriculture.” He attributes the changes to improved collaboration and coordination by the Catchment Management Committee and the Albert Water Management Zone. AWMZ team leader Guma smiles and says: “The advantage of catchment-based water resource water management is that we give the power to the stakeholders. Those who are using the water [decide on] how they want to use the water.” With this revived approach, structures like the Albert Water Management Zone and the Catchment Management Committees not only exist on paper or in offices, but actively and practically fulfil their water resource management mandate.

This article was written by EyeOpenerWorks